Recovering From The Pali Canon: A World Disenchanted (Part 1 of 3)

"This disenchantment of the world didn't appear to be adventitious, but the intended result of a faithful interpretation of the view circumscribed by The Buddha of the Pali Canon."

This three part essay details the pain and glory of my initial encounter with Buddhism through The Pali Canon on a nine day silent meditation retreat and the impact its emphasis on turning away from the world had on my life, draining its particulars of meaning in the pursuit of the transcendent. Afterwards I will explore the road I took to recover from The Pali Canon expanding my conception of the path and recovering a fundamental sense of meaning in the cosmos.

“[the Pali Canon view] erases meaningfulness if it lacks depth. Emphasising the pursuit of the unfabricated disparages the world, erasing the world of phenomena, this does something quite profound to ones sense of meaningfulness. Meaningfulness would only lie in the movement towards ending rebirth or unbinding fabrication if that’s the only conception of the divine or cosmology.” - Rob Burbea

The Initial Encounter

I awoke in the dark to a terror constricting my chest.

Just beyond the porous limestone walls of my room I could hear the soft snores of sleeping retreatants all around me, echoing off the hard surfaces of our shared cottage. I turned to my bedside table to glance at the dim halogen glow of the clockface, it read: 1:15am. I’d had barely three hours sleep.

It was the morning of day five of my first nine day silent meditation retreat, focused exclusively on studying texts from the Buddhist Pali Canon. The study was intensive, each day consisting of a morning and afternoon class (an hour each) followed by another hour of Q&A in the evening. For a yogi brand new to the practice of meditation and study of Buddhism, this was a substantial dose of content to take in and contemplate in the quiet hours between classes, often spent walking in the leafy forest grove surrounding the retreat centre or sitting quietly in the cavernous silence of the hall.

The monk teaching the retreat spoke with a conviction I had never experienced before, his exposition being delivered on the razors edge between a matter-of-fact certainty and religious zeal. The result was that he came off humble and non-needy which gave the teachings the tone of an offering, an invitation into seeing the world in a radically new way, one that was utterly compelling and unique. As the hours went by, I slowly began to open to the possibility that I was encountering something both vital and disturbing in its implications, and slowly, my guard began to lower.

As my hands came down, I quickly discovered that The Buddha of the Pali Canon doesn't pull any punches. At times it felt like the similes would fly off the page and strike the audience with a vicious impact, causing us to collectively wince: we were slaves to craving, seeking happiness where it could not be found, lost and deluded in a futile cyclic existence and wasting our time, our entire lives beyond the practice folly. Some chose to meditate through these blows, sitting like marble statues; upright and serene despite our desperate situation, while others chose to take notes, scrawling furiously in the margins, desperate not to miss a word.

Scanning the room, I appeared to be the youngest by what looked like a few decades and one of the few Caucasians on the retreat. I still recall those tender and exploratory moments during the first evening of the retreat where I watched old friends greet each other in the dining hall with hugs and handshakes and felt out of place, like an outsider who had stumbled into an unfamiliar clubhouse; an overconfident kid trying to talk with the adults in the dinner table.

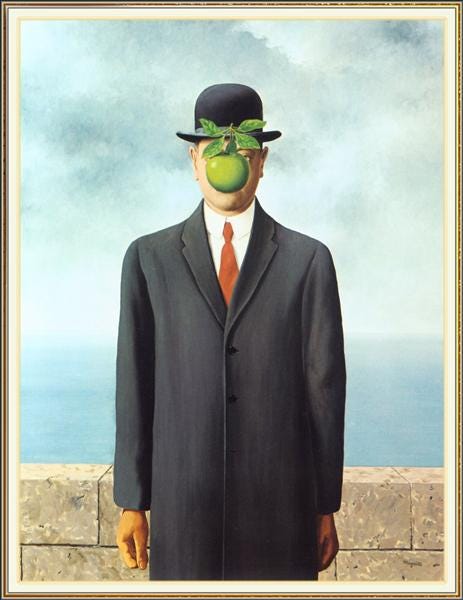

As the hours passed and the view was laid out in excruciating detail I noticed a sense of overwhelm building which I felt powerless to stop, my stomach tying itself in agonising knots. At the dawn of the fourth day the feeling began to reach its crescendo and I felt completely out of my depth, in a league of teaching and practice I wasn't ready for, haunted by the unbroken silence and my innate resistance to the teachings. It wasn't long before I completely lost my balance and slowly withdrew into my thoughts, sitting on the outdoor benches around the retreat centre brooding. A solemn stone gargoyle, eyes downcast, not wanting to be seen, lost in a cloud of thought and yet, due to stubbornness, pride or shear fascination I would not allow myself to leave, I felt that there was something crucial here I needed to understand.

As I lay awake that night, heart slightly trembling, stomach a pit of despair and mind surging, I found myself facing the question: "what if I've had it all wrong?" My life at the time was entirely dedicated to worldly pursuits, pursuits I enjoyed and found meaningful, the kind of pursuits the Buddha repeatedly eviscerates in his discourses.

I was invested in the establishment and progression of my career in IT, exercising and dieting assiduously, running a public speaking club and competing in competitions, going through a tumultuous break-up with a woman I'd loved for eight years (complete with the customary rekindlings), engaged in a vibrant social and family life and perhaps most significantly opening further to my deeply felt necessity for forms of artistic expression. I was writing everyday, taking drawing classes online and had just begun studying music and learning an instrument which I was practicing diligently. I was ambitious and welcoming of novelty and challenge, particularly in my creative pursuits. However, almost all of my energy and momentum was moving outwards into a world which (through these teachings) was slowly losing its colour and vibrancy.

Entry Into The Flat Land

The lens on the cosmos offered by the Pali Canon was rather grey and reductive. Its central thrust being that since beginningless and endless time we have been trapped in a cyclic existence whose very nature is dissatisfaction (or suffering, to use a favored term). Our minds, being deluded by craving and attachment, transmigrate from body to body, and once born again, repeat the entire harrowing cycle over. Starting from the first adolescent heart-break to the eventual painful decay of ones physical form. Not only is this cycle painful but it’s tragic, as the whole process is driven by our deep desire for happiness that we seek to gratify through impossible means, looking for stability where there is only change. The monk called this process 'Samsara' and was explicit that it was bad news to be in it as it was no simple task to get out.

I didn't know it at the time but the teachings I was absorbing through this retreat were surreptitiously ushering me into the flat land. A comos where the particularities of being: manifestation, action, expression, love, personality, art and character are denigrated in the movement towards the universalities: ending rebirth and unbinding Samsara. A cosmos oriented towards transcendence, and to the degree that the view elevated the pursuit of transcendence it denigrated anything less, which at the time, was everything I cared about.

The emphasis was clear, suffering was the name of the game, a thread that was inextricably woven into the fabric of existence. Gone was the possibility of a world pervaded by beauty, depth, profundity and love, the very qualities that added those vital layers of meaning to my experience of the world. From now on, my mind would be keenly attuned to all the ways it fell short, all the ways it disappoints, all the ways it burns.

The implications of this view were deeply challenging, laying siege to my foundational worldview and catalysing a thorough reexamination of my entire mode of being. My priorities seemed absurd in the light of Samsara, a result of delusional grasping at ephemeral forms, like trying to re-arrange the deck chairs on the Titanic. My values simply couldn’t hold against the strength of this view and its repeated validation in my own experience.

Looking back, it was during this restless night that the plug went from under me, the beginning of the slow drain of the once nourishing waters of meaning from my world, swirling in a slow maelstrom down the sinkhole. A drain that would make way for a deeper dedication to the path, a degree of dedication that would eventually lead me to ordain as a Buddhist monastic to practice full-time, but a dedication that would come at a cost. The splitting of my activities into worldly and spiritual, the reluctant turning away from so many of the artistic pursuits I loved and valued, the sidelining of friendships and intimate relationships and the simmering existential dread of being trapped in a burning wheel of fire.

A Way Out: Reenchantment

Fortunately (or unfortunately) through my engagement with monastic communities, Buddhist centres, Dharma discussion groups and practitioners of every order I would discover that I wasn't alone. This disenchantment of the world didn't appear to be adventitious, but the intended result of a faithful interpretation of the view circumscribed by The Buddha of the Pali Canon. Disenchantment was exactly what The Buddha had in mind, and for good reason, as one cannot expect to move forward into his Dharma while being pulled apart by the demands of a tumultuous worldly existence.

But, to paint every aspect of existence with the same brush felt, in some deep part of my being as a fundamental impoverishment. A view too rigid in its boundaries and singular in its emphasis, a view excluding the great depths of potential meaning I had experienced in my everyday sense of things, a view useful in its raw power to turn one inward but parasitic in the long run.

It would be many years after crash landing into the Theravadan tradition before I would be able to open my conception of the path into something more spacious and inclusive, to be able to dispell the crippling tension between loving the particularities of my life while also wanting to transcend them. My first step in recovering from the Pali Canon would start with a shift in emphasis towards emptiness, meeting Nagarjuna and opening to The Great Vehicle: Mahayana Buddhism.